Updated every Monday, Wednesday and Friday ... and maybe other days too.

Wednesday, October 31, 2012

Chunks of memory

So farewell, then, Ceefax. I'll miss it when I'm back in England. We still have teletext here, but it's not remotely as good as Ceefax was. You can't even follow the cricket on it.

After a while I could do it almost with my eyes closed: the newsflash on 150, then all the news from 102 upwards, the regional news on 160, then the football on 302 and pages upwards from that, the cricket on 340 and so on. Then back to 102 and see what had changed in the meantime. This is not a particularly sociable and outdoorsy way to conduct oneself, but neither is playing chess. Or reading about it on the internet.

Monday, October 29, 2012

Chess goes to the movies: The Thing

[Warning: This post contains spoilers]

What do people do when they're stuck in Antarctica with the weather closing in and no means of contacting the rest of human civilisation? Well, we know what they did at United States National Science Institution 4 in the winter of 1982: they hung around the games room playing table tennis, strumming guitars and reading. This we discovered from the opening scene of John Carpenter's The Thing.

Actually, it isn't quite the very first scene. The film opens with a space craft crashing to earth and then, after the title screen, a helicopter chasing a husky across the icy tundra.

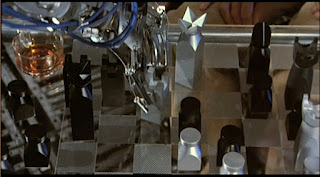

Neither, as it happens, is it quite everybody who's living it up in the mess hall. Macready (Kurt Russell) is in his cabin amusing himself with a bottle of scotch and a Chess Wizard computer.

Let's leave somebody else to administer a sharp kick to the nutsack belonging to whoever was responsible for the chessboard continuity and stick to thinking about the scene's place in the film as a whole. What is it doing there?

Unlike Saturn 3 the appearance of our favourite game in The Thing has got nothing to do with plot. Rather the chess is there, just five minutes from the beginning, to tell us something about Mac's character. Yes he's a drinker and yes he's a loner, but now we know he's also got attitude. He might get beat, but he'll go down in style. That's what those 52 seconds show us.

"You gotta be fuckin kidding"

That's all you need to know about Macready. The Thing is about to destroy his camp and everyone in it. He won't be a match for this strange alien life form so he's going to lose in the end. Still, he'll fight a good fight and when he finally checks out he'll do it with a flourish and a smart line of dialogue or two.

Macready might get beaten, but because he's the kind of guy who tips whisky in the circuit boards he'll never be defeated.

chessboard shots from outpost31.com

Saturday, October 27, 2012

Mr. Rosenbaum's Chess Picture. Part 1: The Tableau

This is how The Chess-Monthly broke the news in late 1880…

But we have rudely interrupted The Chess-Monthly report. Let’s get back to what is barely, in fashion of the day, the beginning of its first paragraph. It continues thus:

...where is sits in the splendour of what, in spite of the "Castle" appellation, and its appearance, is a Victorian mansion. Most appropriate. Beware, though, if you visit to have a look as you could easily miss the tableau, dimly lit as it is, in the shadows of the Billiard Room (and so a word of advice in your shell-like, from someone who has been there: if you want to study the picture, take a torch).

Now, we soldier on with that interminable first para. It cranks up the tension…

'PRIVATE VIEW OF MR ROSENBAUM’S CHESS PICTURE – An event of unusual interest took place on Saturday, the 30th October, at 26, Manchester Square [in London’s West End - MS], the residence of Dr. Ballard. Almost on the eve of our going to press we are unable to give the details in extensio. Nevertheless, as it is our duty to supply our readers in the provinces and abroad with the earliest information possible, we devote as much space as we can spare to do justice to the artist, as a feeble expression of our gratification to see [Mr. Rosenbaum’s] labour of many years crowned with deserved success.'…sentiments that this series of posts humbly seeks to emulate: we, too, will endeavour to do Mr Rosenbaum's picture, and the artist, justice, albeit 130 years later, but near enough to the anniversary of that “event of unusual interest” on 30th October 1880. And we, too, are pleased that once again the good folk reading this blog in the “provinces and abroad” will have to opportunity to join we metropolitan types in the fun and games.

But we have rudely interrupted The Chess-Monthly report. Let’s get back to what is barely, in fashion of the day, the beginning of its first paragraph. It continues thus:

'Several years ago (we think in 1874) Mr Rosenbaum offered to paint a group of eighteen prominent members of the City of London Chess Club, and to present the painting as a prize for a handicap open to all members of the Club. The picture was fairly commenced, but abandoned, owing to the reluctance of most members to join the Handicap. Though Mr. R.’s actual cash expenses were secured to him, he was loath to lose the material he had collected. His severe illness for several years prevented him indulging actively in his twin hobby for chess and painting, but in 1877 he formed a new project, viz.: to paint a fancy chess gathering, which should contain portraits of all prominent members of the English Chess world. Every one to whom the idea was communicated, pronounced it to be impossible of realisation, and if accomplished prognosticated, as to the result, a total failure. But Mr. Rosenbaum, nothing daunted by these prophecies, and braving the difficulty of getting the necessary sittings, the photographs, or even sight of the originals he wished to paint, went to work in earnest, and after three years’ steady application to the task he had set himself, finished the picture…'…and we break-off again for a breather, and a little diversion from that relentless para., the second half of which still stretches yonder. So, at the risk of getting slightly ahead of the story, let’s jump forward 130-odd years. The under-appreciated painting (which we will get to after the necessary preliminaries) of a "fancy chess gathering" is now in the ownership of the National Portrait Gallery, and is currently outposted to the restored Bodelwyddan Castle near Rhyl, in North Wales…

...where is sits in the splendour of what, in spite of the "Castle" appellation, and its appearance, is a Victorian mansion. Most appropriate. Beware, though, if you visit to have a look as you could easily miss the tableau, dimly lit as it is, in the shadows of the Billiard Room (and so a word of advice in your shell-like, from someone who has been there: if you want to study the picture, take a torch).

|

| It's in here; somewhere. |

'[The artist] challenged [all] criticism by issuing the following invitation : - “Mr. A. Rosenbaum requests the pleasure of Mr. --------'s company at the first private view of his “Chess Picture,” at 26, Manchester Square (by kind permission of Dr. W. R. Ballard, Jun), on Saturday, the 30th of October, at which Dr. Zuckertort will play eight games blindfold.” Most of the recipients of this card were, of course, on the tiptoe of expectation, many of them having only seen the picture in an unfinished state a long time ago. Shortly after two o’clock a steady stream of visitors commenced to arrive, and the séance began. On entering the large reception-room one was agreeably impressed by the novelty of the scene. Mr. R. could not reasonably depend on a bright day at this time of year, and had therefore determined to make use of artificial light, though he must have felt convinced of the fact that no painting can be exhibited to the best advantage by such means.'The reader is obliged to conjure the scene in their mind's eye as The Chess-Monthly didn't provide an illustration of Dr Ballard's handsome reception room. The correspondent does a jolly good job nonetheless, and provides this vivid description:

'The west triangle of the room was tastefully draped of with dark crimson curtains, arranged to cover a large square of gas-piping with powerful burners. The frontispiece of this structure bore on the top a medallion with a tied bunch of arrows, encircled by the motto, “Viviat, Caïssa,” and at the bottom the inscription, “A match by telegraph, suggestion for the future.” On the side festoons were fragments of chains, emblematical of the present unfortunate state of disunion in metropolitan Chess circles. These decorations appeared in semi-darkness by contrast with the brilliant centre opening, which poured in its hidden lights on the picture, 6ft. by 4ft., including frame, the effect was startling.'Now, on the tiptoe of expectation as you surely must be, prepare to be startled. Jump to the picture:

Friday, October 26, 2012

Won't find out

When CJ suddenly resigned during the Istanbul Olympiad, I have to confess that my first thought was along the lines of "Thank God! I'll never have to write another word about the duplicitous toerag". It is possible that the thought of never having to read another word about the duplicitous toerag was also not unattractive to many of our readers.

We may scratch our heads about the "better offer" that he claimed to have received, since the projects in which he is presently engaged do not seem to add up to much more than panto rehearsals, and it is, besides, hard to imagine what "offer" would have caused CJ to spend less time on ECF Presidential business than he did in the last year, given that the time which he expended on that business was approximately nil. But never mind, never mind, the main thing was - no more CJ. Gaudeamus igitur.

But life is full of disappointments, and like the proverbial bad penny, albeit a peculiarly expensive penny, CJ has turned up again. Not in person, thank whatever God you may believe in, but in relation to the ECF Council meeting that took place the weekend before last and from which it was reported:

In response to a question from Alex McFarlane, Andrew confirmed that a payment had been made to CJ de Mooi in respect of his trip to Istanbul, but that his total expenses came to significantly more than the amount claimed. Mohammed Amin proposed that the Board should investigate whether CJ adequately fulfilled his role in Istanbul, and seek a refund if it was concluded that he did not. This was approved on a show of hands by 15-12.I admit my first reaction to this intelligence was that it was an absolute waste of time, since the chances of getting a refund out of CJ are no better than the chances of getting the truth out of him. Still, it has the virtue of giving us a small period to ask some useful questions in advance of the usual declaration that there's nothing to see here.

It does seem that CJ managed to terminate his jolly to the Olympiad without attending the FIDE General Assembly* let alone reporting back to the ECF on the event. This would not normally be considered an adequate degree of performance in discharging an official's duties, a shortfall which would be exacerbated if, as is suggested, it was known before the event started that CJ intended to resign. Which does raise questions not just as to whether monies were received for duties that were unperformed, but whether they were actually asked for in good faith.

You know, in normal circumstances, I reckon it would be considered a serious embarrassment if you shelled out a wedge of money to somebody to go to an overseas meeting which they were not obliged to attend, and they skipped away without actually (or properly*) attending the meeting - but, nevertheless, kept the money. Especially if you had already had all sorts of problems involving that particular individual and untraceable sums of money.

More so, even, if the reaction to the previous episode had been that yes, it was unfortunate, but lessons had been learned, it won't happen again, now everybody needs to move on. Now I don't doubt the sincerity of this - of the desire to get things right and do better in the future - but the point remains that if I wished to demonstrate that I had learned not to hand over sums of money to CJ de Mooi for him to use irresponsibly, I would probably not seek to do so by handing over another sum of money to CJ de Mooi for him to use irresponsibly.

But how much was handed over into CJ's sticky mitt? I am afraid that, not for the first time, I do not know. Because nobody is telling. I rather wish they would. It matters. I mean if there's been a mistake - and there surely has - how are we supposed to come to any judgement on the importance of that mistake if we don't know how much money it involved?

See, with the untraceable money from Sheffield, if it were just fifty quid which can't be matched with paperwork, then maybe we could say all right, these things happen, it's not so important. But if it were ten thousand quid, that's a different story, isn't it?

As with Sheffield, so with Istanbul. If we divvied up twenty-five quid, I'd take a different view than if the sum were, say, five hundred.

I can tell a monkey...

Thing is, I do actually pay towards the costs of the ECF. It's not an atrocious amount, far from it. But it does mean that I am among the collective group of people of whose money we are speaking, when we say that we appear to have flushed an unspecified amount of it down the toilet for the benefit of CJ de Mooi's holiday and networking opportunities.

....from a pony

So to me, it matters how much. But it also matters because you do not achieve a proper state of financial organisation and rectitude without thinking that figures matter. If you don't think that figures matter, you will not have your financial house in order. And the first responsibility of any organisation is to have its books in order. This is so whether it be the English Chess Federation, the Coca-Cola Company or the People's Front of Judea.

But everybody understands that now, don't they? Everybody understands that monies have to be traceable and accounted for. We all know that now. There is no need to labour the point.

Or maybe there is. Because it turns out that the ECF's accounts are still not properly in order.

Yes, they're working on it - and I mean that without irony. Still, I raised an eyebrow when I heard. And I raised the other when I saw the minutes from a recent ECF Board meeting. See this page, scroll down to Meetings / Minutes and click on the link for Board Meeting No 63 August 2012. [NOTE: since this piece appeared the link has mysteriously ceased to function.]

Under

15 Update on actions from Finance Committee's Report

there is a striking passage:

"Comfortable"? What is this "comfortable"? There is no "comfortable". There are proper records and then there is "comfortable". If there are no proper records, what you have is crossed fingers and a prayer. Not "comfortable".

That's what proper records are for. That's why they're required.

The only way you really can be comfortable that there has been a contribution from X is because you have a document from X to say so. No document, no comfortable. And this is so even where X is a reliable individual, which is not true of every X I can think of. Otherwise, you can use the word if you want, but it invites the response - on precisely what basis are you "comfortable"?

So personally, I'm not comfortable that these lessons, that we were assured had been learned, have in fact been learned. And I'm not comfortable that the best way of preventing bad things happening again is to complain that people told us they were happening.

Those who do not learn from history are condemned to pretend it didn't happen (or something like that)

But that's another subject I've written too much about, you may be thinking. You know, you might be right. What can you do? These things keep on happening. It's the normal consequence of being in denial.

Anyway. CJ's Turkish jaunt. I really wouldn't mind knowing:

- what he did there

- whether he reported back on what he did

- whether it was known beforehand that he was planning to resign

- how much he was paid in expenses

- how much the ECF proposes to ask him to pay back.

Because I paid for that trip. And because lots of people paid for that trip. And for lots of other good reasons. And because we were supposed to do better the next time.

[* CORRECTION - apparently he attended the first morning.]

[Banknote image: Banknote World]

[CJ index]

Wednesday, October 24, 2012

Sixty Memorable Annotations

#12: Judit Polgar - Veselin Topalov, San Luis 2005

I really rather like the concept of a knight that only looks good. It sounds a little odd, but I guess the point is that White is doing the sort of thing that you’re usually supposed to be aiming for - sticking a knight on a secure central square - but in that specific position it just happens not to be particularly useful.

I must admit I don't know what Cheppy's got against like plonking the knight on queen five. Even after seven years to think about it, Polgar's 16 Nd5 still looks OK to me. Anyhoo, it's the general idea that interests us today, 'moves which appear good but aren't' being the exact opposite of what the Simon Williams' latest DVD is all about. Crash Test Chess II: Thinking Outside of the Box covers is full of ideas that look stupid or outright absurd and yet, on closer inspection, they turn out to deliver precisely what the position needs.

CTC2 is the latest in the Ginger GM's series of '£5 for one hour' DVDs. What you get on this one is a total of seven positions in which the player to move employs a surprising, 'outside-of-the-box' idea. Three knight manoeuvres that ignore the general advice about rim and dim, three bishop moves that seem to have no point at all and to round things off, a spectacular idea from Keith Arkell.

More experienced chessers might find some of the material rather familiar, but I suspect most folk will find much to interest them. Actually, although we've had two of Williams' positions on the blog before, I found I only knew one of the seven well. Two I half-remembered and had heard of a fourth. The other three, however, I don't recall seeing before anywhere at all.

If I have one criticism it's that the move to be played is shown on screen before the position appears. This isn't as serious as it might have been. The recurring themes and the fact that you know you're looking for something beyond the norm means you could guess half the moves at a glance anyway. Still, to get the most out of CTC2 I'd recommend keeping your eyes closed whenever you hear the theme music playing. That way you can have a think for yourself before the GingerGM starts explaining what's going on which I'm sure must be better from a training point of view.

Any decision to purchase a chess DVD is an implicit acceptance of the fact that pound-for-pound you end up with less material than you would get in a book. Video remains a hugely popular medium amongst chessers nevertheless - just take a look at the shelves next time you wander into Malc's Chess Emporium - presumably because of a perception that studying the game in this way will aid retention of the information covered.

As a result, it seems to me, the presenter's style is vital to the success of this kind of product and I've never undertsood those folk who seem willing to accept a boring delivery from somebody who looks ill at ease in front of the camera. Needless to say - needless, that is, if you've seen any of Williams' previous DVDs - there are no such concerns here.

At a fiver a pop I bet there'll be quite a few people willing to give Crash Test Chess a go. Having seen one for myself, I'd be surprised if most of those who do try one don't find themselves buying others in the series too.

16 Nd5

At first sight a strong move, but the knight only looks good on d5.

Ivan Cheparinov, New in Chess (2005, #8)

I really rather like the concept of a knight that only looks good. It sounds a little odd, but I guess the point is that White is doing the sort of thing that you’re usually supposed to be aiming for - sticking a knight on a secure central square - but in that specific position it just happens not to be particularly useful.

I must admit I don't know what Cheppy's got against like plonking the knight on queen five. Even after seven years to think about it, Polgar's 16 Nd5 still looks OK to me. Anyhoo, it's the general idea that interests us today, 'moves which appear good but aren't' being the exact opposite of what the Simon Williams' latest DVD is all about. Crash Test Chess II: Thinking Outside of the Box covers is full of ideas that look stupid or outright absurd and yet, on closer inspection, they turn out to deliver precisely what the position needs.

CTC2 is the latest in the Ginger GM's series of '£5 for one hour' DVDs. What you get on this one is a total of seven positions in which the player to move employs a surprising, 'outside-of-the-box' idea. Three knight manoeuvres that ignore the general advice about rim and dim, three bishop moves that seem to have no point at all and to round things off, a spectacular idea from Keith Arkell.

More experienced chessers might find some of the material rather familiar, but I suspect most folk will find much to interest them. Actually, although we've had two of Williams' positions on the blog before, I found I only knew one of the seven well. Two I half-remembered and had heard of a fourth. The other three, however, I don't recall seeing before anywhere at all.

If I have one criticism it's that the move to be played is shown on screen before the position appears. This isn't as serious as it might have been. The recurring themes and the fact that you know you're looking for something beyond the norm means you could guess half the moves at a glance anyway. Still, to get the most out of CTC2 I'd recommend keeping your eyes closed whenever you hear the theme music playing. That way you can have a think for yourself before the GingerGM starts explaining what's going on which I'm sure must be better from a training point of view.

Rumours that the world number 18 recently purchased a copy of CTC2 remain unconfirmed

Any decision to purchase a chess DVD is an implicit acceptance of the fact that pound-for-pound you end up with less material than you would get in a book. Video remains a hugely popular medium amongst chessers nevertheless - just take a look at the shelves next time you wander into Malc's Chess Emporium - presumably because of a perception that studying the game in this way will aid retention of the information covered.

As a result, it seems to me, the presenter's style is vital to the success of this kind of product and I've never undertsood those folk who seem willing to accept a boring delivery from somebody who looks ill at ease in front of the camera. Needless to say - needless, that is, if you've seen any of Williams' previous DVDs - there are no such concerns here.

At a fiver a pop I bet there'll be quite a few people willing to give Crash Test Chess a go. Having seen one for myself, I'd be surprised if most of those who do try one don't find themselves buying others in the series too.

Review copy of Crash Test Chess 2 supplied by GingerGM.com

Monday, October 22, 2012

Spite and Malice

Ha ha! Revolution!

We live in a country where over 100,000 people can march on Parliament and none of the Sunday newspapers carry it on their front pages. We live in a country where George Osborne can make an arse of himself on a train and everyone ignores the dreadful ongoing events in Cardiff. Apparently, we also live in a country where good people are consistently turned down for leading roles within the English Chess Federation.

ECF Council watch Adam Raoof go

You can play your card, I'll hold on to mine

Peering in at the UK media, there's a discernable layer of foundation to mask the splodge underneath. A scrotum to protect the bollocks, if you will. At the ECF they hang loosely, seemingly not caring about the fragility of their position or how ridiculous they look. As I see it, for Adam Raoof to be defeated by None of the Above for a role that is absolutely necessary to fill competently, and where he has all the attributes for such a role, is due to nothing more than spite. Many of the people at that meeting got out their Tupperware and gorged on the foil-wrapped wave of vitriol documented over the past few months. I suppose I shouldn't be surprised that the gutter commentariat are listened to.

Everything will blow tonight

Either friend or foe tonight

Adam's lack of manifesto or appearance at the AGM appears to have been a regular complaint. However, if votes went west for that reason, those who changed their mind on the day may wish to consider why he wasn't there. The Golders Green rapidplays Adam runs are a staple of the British chess scene, particularly at the grass roots level, which is the primary group that someone responsible for marketing and membership needs to be able to deal with.

I think it's commendable that he committed himself to running his tournament instead of attending a vote against nobody. Chess benefited. At least, it did until the vote was cast.

Italics are lyrics from Spite and Malice by Placebo. Copyright Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC.

Saturday, October 20, 2012

The beginnings of organised chess: Brasen Nose Chess Club 1810-11, part 6 of 6.

We have now reached the final part of our exploration of the

short-lived Brasen Nose Chess Club in Oxford and the time has come to reflect and

ask what, if any, conclusions we can draw about the first flowering of chess

clubs in Britain.

The founding of Brasen Nose Chess Club in late 1809 or early

1810 predated the next earliest known provincial club, Hereford Ipswich had a club by October 1813 and a Manchester Liverpool

around 1813/14 when the Liverpool Mercury

carried a chess column.

We now have detailed knowledge of the membership of both the

Brasen Nose and Hereford

This was ‘social networking’, Georgian style. The Hereford

Chess was to become a popular pursuit for men-of-the-cloth

in the later 19th century, and maybe some of those legions of Victorian

chess-playing parsons had belonged to now-forgotten chess clubs in their

college days.

Readers of the series

of blogs that Martin Smith and I wrote about Thomas Leeming’s paintings of the Hereford

The Hereford chess club, as portrayed by Thomas Leeming in 1815.

Courtesy of the Hereford Heritage and Museum Service ©

Had Leeming painted the Brasenose chess gents, they would

probably not have looked so different – young, well-turned-out, confident men

from affluent backgrounds with promising futures ahead of them. Men who were comfortable

in each other’s company.

Interestingly, Leeming was in Oxford Oxford

There is another intriguing, if circumstantial, link between

the Brasenose and Hereford Hereford Hereford

Henry Matthews: the Hereford

Pencil and watercolour portrait by Joseph Slater.

Brasen Nose and Hereford Britain Hereford

Could it be that in college rooms, town houses, country

estates, hotels and public meeting rooms around the country, small groups of

gentlemen were getting together to share their passion for the game? We can

only speculate, but it does seem that there was a wave of enthusiasm for the

game around this time. The London Chess Club had opened successfully in 1807,

and prominent figures such as Napoleon Bonaparte and even the king himself,

George III, were helping to popularise the game across Europe .

Nothing better to do than play chess:

an 1816 lithograph

of Napoleon during his exile on the island

of Saint Helena

Rules were being rationalised and standardised, and Europe’s

leading players were giving exhibitions and coaching talented amateurs

including William Tuckwell, founder of the Brasen Nose club (as we noted in the

second blog in this series). And there was a growing appetite for

chess books. In one of the versions of Thomas Leeming’s paintings of the Hereford

The gentlemen of the Brasen Nose and Hereford

See the earlier posts in the series here.

Series credits

Thanks to:

Brian Denman, who started all this off by telling me that

the Brasen Nose Chess Club minute book might still survive at the Bodleian.

Martin Smith, who read my drafts and kindly undertook the considerable task of entering

them into this website.

Main sources:

Martin Smith & Richard Tillett :

Every

Picture Tells a Story, a series of 21 blogs about Thomas Leeming’s

paintings of the chess club at Hereford

Philip Sergeant: A

Century of British Chess.

B Goulding Brown: British

Chess Magazine October 1932.

Rev. William Tuckwell: Our

Memories: Shadows of Old Oxford, a copy of which is filed at the Bodleian

Library with the Brasen Nose Chess Club rules and minute book.

Rev. William Tuckwell: Reminiscences

of Oxford

(this has been digitised and is available here).

The rules and minutes of the Brasen Nose Chess Club,

Bodleian Library ref: MS. Top. Oxon. e.

159.

Tim Harding: Which are the Oldest Chess Clubs? on ChessCafe.com.

Friday, October 19, 2012

Once was enough - or maybe it wasn't : The Berlin Wall

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bb5 Nf6 4.O-O Nxe4 5.d4 Nd6

Writing the Once Was Enough sequence is not, I should say, a pledge that I will never again play any of the openings it features. A man is not on oath in a trivial internet chess series.

Still, I'm happier including nonsense like the Portuguese Gambit than something like the Chebanenko Slav which I can easily imagine myself picking up again, even if only by transposition. That's why I've havered about including the Berlin Wall, and why in the end - in the spirit of being unable to make up my own mind - I both have, and haven't. Look at this column as an interlude in the series rather than an addition to it.

Wednesday, October 17, 2012

Bashing Boris

If you're going to release a new DVD I supppose it doesn't hurt if you score the best result of your life the same weekend. Last Friday I received a review copy of Simon Williams' Crash Test Chess II: Thinking Outside of the Box and then just a couple of days later the GingerGM knocked over recent World Championship challenger Boris Gelfand at the European Club Cup.

Williams says his DVD covers, "some amazing moves, some interesting moves, some unusual moves ... basically some very funky stuff", but I'll get back to that next week. Today, we'll stick with how he smacked up the Gelfmeister.

Well that wasn't too shabby was it boys and girls? Three questions:-

1.

Is this the best individual result achieved by an English chesser playing Black since Miles beat Karpov?

2.

Is it interesting or amusing that Yankidoodle world number five Hikaru Nakamura bottled Williams' Classical Dutch yesterday and opted for the Exchange French instead?

3.

(Bit of a preamble for this one)

Williams' win over Gelfie was highly reminiscent of his 2003 defeat of Romanian GM Dragos Dumitrache. Actually, move White's queen back to d1 and return Black's bishop to e7 and the position reached at move 11 in Sunday's game would be identical to the earlier one at move 10.

Have a look at that game from Montpellier ten years ago. 28 moves and White doesn't move his queen once.

Is that a record?

Monday, October 15, 2012

The Fake Sound Of Progress

"Never confuse movement with action."

Ernest Hemingway

Progress. Soapy, soapy progress.

Having spent all of Friday afternoon being herded into a valley of unhappiness in the name of Marxian theory, and having watched Mehdi Hasan veritably implode this weekend, I'm feeling fighty. I'm also in a dangerously rational state of self-awareness and, all right, it probably wasn't a wonderful idea to get up at 6:30am for Sunday's predictably dull Korean Grand Prix.

In short, I'm knackered.

Still, let's have a cheery discussion on the nature of progress within chess, shall we?

Black's just played 7...b5, winning a piece for two pawns.

And now, after 20. c5, the material balance is the same. But which player has made progress? Has either?

Guaranteed victory or guaranteed defeat?

Objectively, given they've hoovered the queens off and white's kingside isn't coming to help its centralised friends any time soon, black's improved their position. But what's the point of that if they're uneasy? After the opening disaster, white has very little to lose and might as well go for it, which they have done.

Richard James' advice to "look, not think" applies here. Because, aaah! the pawns and aaah! my king and aaah! I've been completely winning since the opening and if I don't win this everyone will laugh at me and I'll probably lose all my confidence and aaah! my confidence is waning already and aaah! aaah! aaah! DRAMA!

And breathe.

I think a state of progression exists largely in the mind. In general life terms, if I can't look back at myself from 12 months ago and wonder what on earth that person stood for, I know I'm going nowhere. This is unhelpful in chess because it's results-oriented and, however much we protest otherwise, the journey matters little to the outcome. If we can find the crudest possible way of reaching a desired outcome, we will.

"But how do I make progress?" should be a question reserved for quiet contemplation on the bus. Within a chess game, in precarious positions such as the above, I prefer this:

"How do I win?"

Saturday, October 13, 2012

The last hurrah: Brasen Nose Chess Club 1810-11, part 5 of 6.

Last Saturday we looked at the internal bickering which was

to be the undoing of Britain Brasenose College Oxford

Sixteen people attended the dinner including guests, or ‘strangers’ as the minutes describe them. In his Reminiscences of Oxford, the founder’s son William Tuckwell reveals the identity of three of these guests: Henry Matthews, Sir Christopher Pegge and a Mr Markland. Henry Matthews was later to achieve considerable success with his Diary of an Invalid, an account of a tour inPortugal Italy France Oxford Lancashire .

Dunbar ’s poems were handed about

in manuscript rather than published and his Ode

to Caissa, which he wrote for the occasion of the dinner, is one of the few

survivors. The text of his ode was transcribed in the Brasen Nose Chess club’s minute

book and later published by Tuckwell in an appendix to his Reminiscences of Oxford.

Although the members had fallen out amongst themselves, they

remained on good enough terms to proceed with the anniversary dinner, which was

held on 14 February 1811 .

The dinner was paid for out of the fines collected from club members for failing

to turn up for club nights or, worse still, forgetting to bring the book of

fines. It was this arrangement that had caused so much dissension, and the

members may have known that their club was unlikely to survive for a second

anniversary dinner, but they made sure they went out in style.

The dinner was held at the King’s Arms, which is still there

today and is now a Youngs pub with its own Wikipedia entry.

The King’s Arms, a popular watering hole for students then as now,

and venue for the Brasen Nose Chess club’s anniversary dinner in 1811.

It stands at the corner of Parks Road and Holywell Street.

Sixteen people attended the dinner including guests, or ‘strangers’ as the minutes describe them. In his Reminiscences of Oxford, the founder’s son William Tuckwell reveals the identity of three of these guests: Henry Matthews, Sir Christopher Pegge and a Mr Markland. Henry Matthews was later to achieve considerable success with his Diary of an Invalid, an account of a tour in

The star of the anniversary dinner was Thomas Dunbar, the

chess club’s poet laureate. Dunbar is a largely

forgotten figure now, remembered only, if at all, for his not-notably-distinguished

tenure as Keeper of the Ashmolean

Museum Oxford Dunbar was well known in Oxford

So, picture the scene at The King’s Arms… The eight members

of the chess club, their differences forgotten (at least temporarily) have

gathered with their poet laureate Thomas Dunbar and their seven guests. Dunbar rises to recite his ode. It tells the story of Caissa,

the Goddess of Chess, (who has her very own Wikipedia entry here) from her origins

in the East to conquer Europe and vanquish

lesser games.

Ode to Caissa by

Thomas Dunbar

From the bright burning lands and the rich forests of Ind

See the

form of Caissa arise;

In the caverns of Brahma no longer confined,

To the

shades of fair Europe she flies.

A figure so fair through the region of light

All natives with wonder survey,

As her varying mantle now darkens with night,

Now beams with the silver of day.

All natives with wonder survey,

As her varying mantle now darkens with night,

Now beams with the silver of day.

Let Whist, like the bat, from such splendour retire,

A splendour too strong for his eyes;

A splendour too strong for his eyes;

The Trump and Odd Trick let dull Av’rice admire,

Entrapped by so paltry a prize.

Entrapped by so paltry a prize.

Can Finesse and the Ten-Ace e’er hope to prevail

When Reason opposes her weight,

When inviolate Majesty hangs in the scale,

And Castles yet tremble with fate?

When the bosom of Beauty the throbbing heart meets,

And Caissa’s the gay Valentine,

What Chessman, who’d tasted such amorous sweets,

His Mate but with life would resign?

But ‘tis o’er – Terebinth the decision approves,

And Whist has contended in vain;

To the Mansion of Hades the Genius removes,

Where he gnaws his own counters in pain.

When Reason opposes her weight,

When inviolate Majesty hangs in the scale,

And Castles yet tremble with fate?

When the bosom of Beauty the throbbing heart meets,

And Caissa’s the gay Valentine,

What Chessman, who’d tasted such amorous sweets,

His Mate but with life would resign?

But ‘tis o’er – Terebinth the decision approves,

And Whist has contended in vain;

To the Mansion of Hades the Genius removes,

Where he gnaws his own counters in pain.

On Philosophy’s brow a new lustre unfolds,

Mild Reason exults in the birth;

His creation benign Father Tuckwell beholds,

And Steph gives the chaplet to Mirth.

Mild Reason exults in the birth;

His creation benign Father Tuckwell beholds,

And Steph gives the chaplet to Mirth.

Three of the club members are referred to in the last two

stanzas: ‘Terebinth’ is a nickname for John Lingard, ‘benign Father Tuckwell’

is the club’s founder William Tuckwell, and ‘Steph’ is Richard Stephens. The

meaning of the last line is lost to us, but the diners that night would have

understood and no doubt rewarded Dunbar with a

knowing chuckle and an enthusiastic round of applause.

The dinner was also the occasion for the club to present Dunbar , who was shortly to travel to the East, with a

letter in Latin drafted by another of the club members, Ashurst Turner Gilbert.

Dunbar was to give the letter to Abdul Hamed

Abraschid, who gloried in the title ‘Father of the Faithful and President of

the Chess Club in the Eastern World’. My internet trawl has revealed nothing

about this splendid gentleman’s identity but research continues and more on

him, hopefully, in a future post.

Next Saturday, in the last of this series, we will review what

we have learned about early chess clubs and consider some intriguing links

between the Brasen Nose and Hereford

Links to the four previous episodes can be found here.

Links to the four previous episodes can be found here.

Friday, October 12, 2012

The Society Of The Spectator

[Note to readers: the site from which most of the following screenshots are taken has been taken down. A call to the Spectator Events office is rewarded with the information that the event has been cancelled due to lack of interest - ejh]

What are you doing at the weekend? Going to the ECF Council meeting, perhaps? Best of luck to you if you are, but if you feel the need for some R&R on the Sunday, why not go along to the Spectator Chess Festival?

What are you doing at the weekend? Going to the ECF Council meeting, perhaps? Best of luck to you if you are, but if you feel the need for some R&R on the Sunday, why not go along to the Spectator Chess Festival?

Wednesday, October 10, 2012

Chess goes to the movies: Saturn 3

[I should warn you that this post contains spoilers. However, there's nothing here which hasn't already been published elsewhere on the web and anyway there's nothing I could possibly write which would spoil the film any more than Lew 'Lord' Grade did when he made it.]

Benson"I teach him as much as I choose."

Adam"You haven’t taught him enough. Sacrifice. It’s one thing you can’t teach them, captain. Sacrifice!

Checkmate."

Saturn 3 (1980)

Last week Chess went to the movies. We had ten quotes from film scenes in which the game appears and you, our esteemed and valued readers, identified nearly all of them.

The lines above were one of only two films you didn't spot. I can't say I was tremendously surprised. They do come from a pretty obscure film, after all. Actually, as far as I can tell there's just one single notable thing about Saturn 3: it is one of the worst movies ever made

That said, Saturn 3 does contain a more than decent chess scene. Perhaps we can forgive it some of its more heinous crimes against film-making.

It's impossible to overstate the extent to which Saturn 3 is abysmally piss-poor. There's the absurd opening sequence, the sets that make Blake's 7 look like The Matrix and, by far the worst of all, the beyond-implausible-crossing-over-into-unseemly relationship between Adam, played by Kirk Douglas (64 when the film was released), and Farah Fawcett (early 30s)'s character, Alex.

Adam and Alex live alone on Saturn's third moon. What the film wants to believe it's showing you is Harvey Keitel pitching up as psychopathic spaceman Benson to shatter their domestic bliss. What the audience actually sees, however, is somebody getting in the way of a leathery old perve fapping around after somebody much too young for him. It doesn't help that Fawcett was evidently told to portray Alex as having the sort of mind and personality normally found in a pre-pubescent child. Precisely what kind of romantic relationship the makers of Saturn 3 thought they were showing is hard to imagine, but I'd wager anybody watching the film today will find it impossible not think of Jimmy Saville.

Astonishingly, Martin Amis - yes, that Martin Amis - wrote the script for the Saturn 3. I'm afraid to say it's just as awful as everything else about the movie. It's amazing how many gems spewed from the Amis typewriter during one single piece of writing. For example,

You have a great body. May I use it?

and,

That was an improper thought leakage.

and last but not least, there's my personal favourite,

No taction contact.

You mean "don't touch"?

Correct.

If that's how people are going to speak in the future then frankly I'm rather glad that the human race will be starving to death, as per the film's premise. I digress, however, because while Amis might have mostly penned a total stinker, the point of today's post is to give credit where it's due. Our man made a very decent fist of the three minutes ten seconds in which Adam, Alex, Benson and Hector the Homicidal Robot play chess.

The chess in Saturn 3 is pretty simple in itself. Adam and Alex are playing when Benson and Hector come along. Adam challenges the bloody iron monster to a game so Alex, who had been winning, steps aside to watch. Presumably this is on the grounds that she is just a girl.

Anyhoo, Hector learning by 'direct input' from Benson's mind, initially does well. "Exchange and simplify" is the instruction that he receives and it seems that Metal Mickey might actually triumph until Adam suddenly sacrifices his queen to win the game.

Nothing exceptional then, but Amis uses the chess to set up Saturn 3's finale. Later Hector is going to go on the rampage and Adam will offer Alex as bait in a trap to bring the robot down. Unfortunately his plan is now going to fail because the idea of giving up a queen to win a bigger prize has been planted in Hector's memory banks. Later still, at the very end of the film, we will recall Adam's words about sacrifice once again as we watch him give up his life to destroy Hector, thereby allowing Alex to escape to Earth.

How's about that then?

So no, it's not exactly Shakespeare. Even so the chess scene works well and it does so because, unlike most of the rest of the film, the presence of our favourite game has a point. It has a relevance which magnifies the impact of later plot developments and Saturn 3's closing scenes.

It's curious, though, isn't it? Chess is generally considered to be too complicated to explain to a lay audience for tournaments to be shown on mainstream television these days and yet the game is the only thing in the film that makes any sense at all.

chess scene images from propmasters.net

Monday, October 08, 2012

And Smith Must Score

Let's dredge up this one again. Why not? Chess isn't recognised as a sport; not by the IOC, not by the British Government, not by most people. But I'm going to suggest, with my tongue gently brushing my cheek, that it's because of a lack of famous commentaries.

Smith didn't score

Name a sport.

"Er...Formula 1, Jeff."

All right, then.

Coulthard self-mates

Such commentary only exists because of the media coverage existing. And it exists because there's a market for it, and because people like Murray Walker and Martin Brundle can keep an audience enthralled through even the boring stuff. Last week, on his 5Live show, Danny Baker started a feature called 'Retired footballers read the dull bits from erotic fiction'. The cult of personality in football exists because of the saturation of media coverage and the opportunity to develop a relationship with the key protagonists. In chess, well, no.

And here's the problem, which, as far as I can make out, isn't going to be solved any time soon. Poker works on TV because the narrative of a tournament or cash game doesn't require an explanation of the whole. It's possible to broadcast only the key moments as every individual hand is a distinct entity. What the viewer sees as a 45 minute rollercoaster was actually filmed over many, many hours. I'm not convinced such an approach is possible in chess because, at the elite level, the concepts themselves will take a long time to explain properly. And commentating on blitz games, while exciting, doesn't leave time for decent explanation, nor is it an indicator of what chess is really about. Though I'll admit that I could listen to Maurice Ashley all day.

I suppose, if that's the only way of making it accessible, then chess is probably better off not being in the mix.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)